Ah, inappropriate. My least favourite word in the whole of the English language.

But the English language has over a million words. Why do I hate that one so much? (Especially since it’s used 29 times in this article?)

Because I just don’t get it.

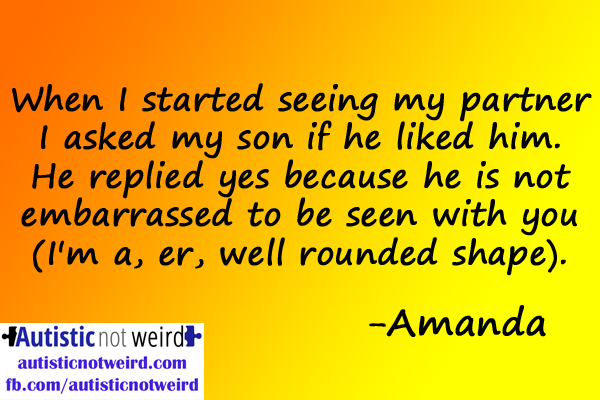

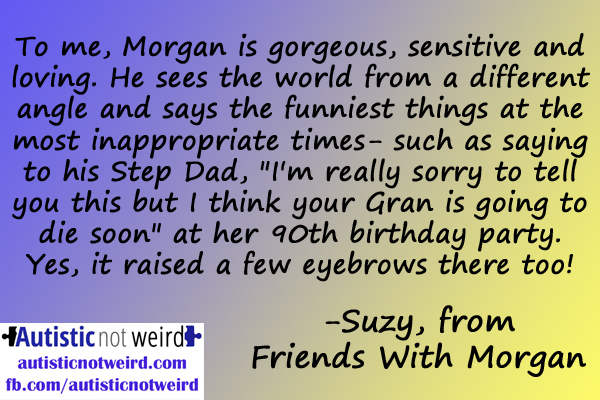

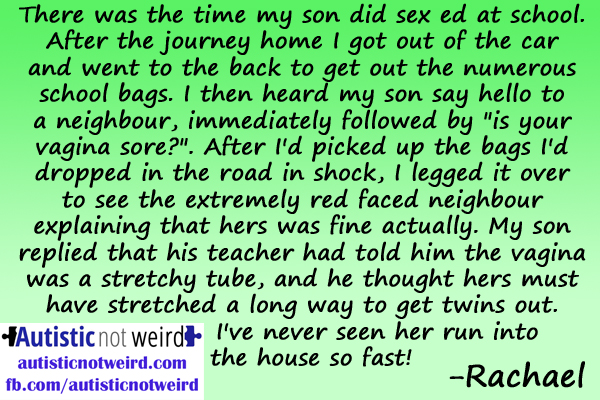

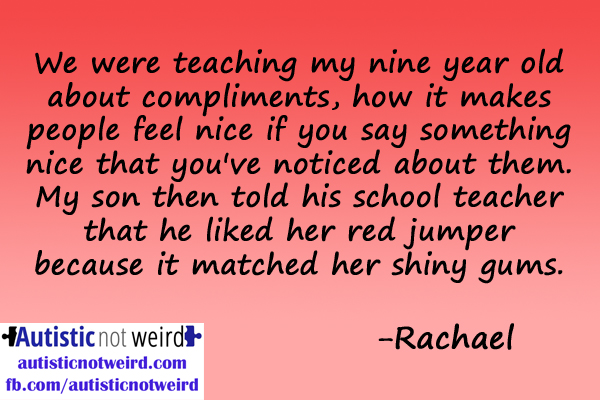

And of course, plenty of other autistic people struggle too. On Autistic not Weird’s Facebook page [all links open in new windows] I asked people if they were willing to share some of their stories about themselves or their kids doing something inappropriate without realising.

The results were amazing.

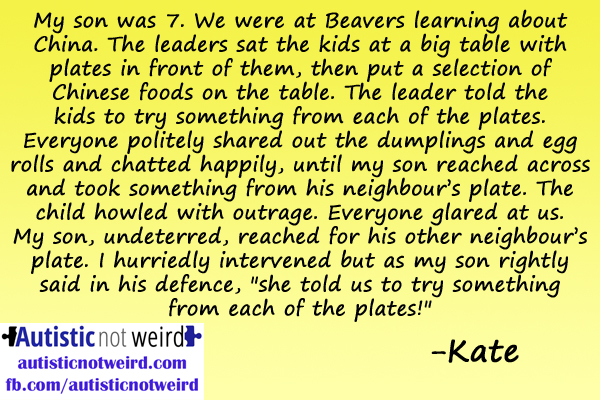

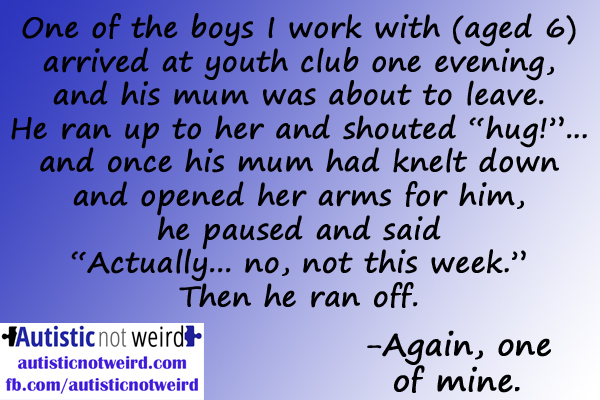

So, the pictures in this article will be made exclusively from their stories. [2021 edit: Oh, and apologies for the use of the puzzle pieces in these pictures. I wrote this way back in 2015 before I realised – and before society started to realise – the problematic nature of using the puzzle piece to represent autism. Even autistic advocates have to evolve and progress as the years go on.]

As a child, every time I got interrupted I’d start my whole story again right from the start. That annoyed people, so in their eyes I was being socially inappropriate. (You know, kind of like interrupting people mid-story. That’s inappropriate too, but they were older than five so they could get away with things like that.)

In all fairness though, people stopped interrupting me pretty quickly once they learned I always started the whole bloody story again. Inappropriate or not, it worked!

These days, I’m an adult who goes really really high on park swings, rather than just sit back and watch the kids do it. Nobody has ever been able to explain why it’s inappropriate for me as an adult to have a go too. It just is.

I’m a person who has no problem discussing religious beliefs in large groups. It’s ‘inappropriate’ to talk about it here in Britain, but nobody can tell me why. It just is.

I’m also that dinner guest who takes the last potato rather than let it go to waste, once it becomes obvious that it’s just going to get thrown. Nobody has ever convinced me why wasting food is ever seen as appropriate, or why taking the last potato is a bad thing when literally nobody else in the world wants it. It just is.

I actually went into a nice rant about the ‘last potato problem’ in a recent talk I did. Watch from 1:44.

[2018 edit- that was actually the second talk I ever did, way back when I was new to autism advocacy. Three years later I ended up flying over to Australia and speaking at Sydney Opera House. And in that talk, once again, I went on exactly the same rant about the last potato. Evidently it’s something very important to me.]

The problem with ‘inappropriate’

Now, very shortly I’m going to answer the titular question and attempt to explain why ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ are tricky for autistic people. But before I do, two reasons why I shudder whenever I hear my least favourite word in the dictionary.

Reason 1) In my experience, people often use ‘inappropriate’ as a synonym for ‘I don’t personally like this so I want everyone else to stop it’.

And that’s the magic of ‘inappropriate’: you can cast it like a wizard’s spell. Just take something you have a personal dislike for, slap the grand title of ‘inappropriate’ on it, and it bans everyone else from feeling able to do it themselves.

(If you doubt me, try it yourself. In fact, take the last potato at dinner whilst saying “I don’t like wasting food. It’s inappropriate,” and see whether anyone dares to object.)

Reason 2) People often use appropriateness as a substitute for morality.

People, generally speaking, know the difference between right and wrong.

They also know the difference between appropriate and inappropriate.

But not everyone seems able to distinguish between right/wrong and appropriate/inappropriate.

I remember plenty of times when I fell short of other people’s appropriateness standards, and was made to feel as if I had done something morally wrong.

You may notice, both of those reasons related to how other people treat appropriateness. Neither of them describe any problem with the words existing. ‘Appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ should exist, but they should exist in much more accessible ways than they currently do.

Anyway, presumably everyone opening this article wanted actual answers to the question. So…

Why do autistic people struggle with ‘inappropriate’?

I can think of four reasons.

- Appropriateness is fluid.

- Appropriateness is discreet.

- Appropriateness is vague.

- Everyone has their own definition of ‘appropriate’.

I’ll cover them one at a time under their own headings.

Note that ‘because we’re deficient’ is not one of the reasons. Just because our understanding of appropriate is different to yours doesn’t mean we have to be wrong!

Now, the detail.

Appropriateness is fluid.

Like many kids, I grew up placing a lot of value on right and wrong. And, like many kids, I was hilariously inappropriate at times.

And remember that bit about how adults get right/wrong and appropriate/inappropriate mixed up? Well it took me until I was 18 to notice it… although clearly I noticed it quicker than many of these adults.

My main issue with using appropriateness as a form of morality is this:

Right and wrong have been the same for thousands of years (by and large). Yes, evolving cultures have changed our attitude towards certain things over the years, but killing and stealing have always been wrong, whereas kindness and charity have always been right.

There’s a lovely sense of consistency about right and wrong, which is another reason why it’s so appealing.

Meanwhile, appropriate and inappropriate can depend on:

- What time of day it is.

(Drink alcohol at 11am and it’s inappropriate. Drink it at 9pm and it’s fine. Kill someone at either of these times and it’s wrong.)

- What time of year it is.

(Dressing in fewer clothes is fine in the summer. In winter it becomes inappropriate. Give money to charity at any time of year and it’s still a good thing to do.)

- What decade you’re in.

(Swearing is far more acceptable in the media these days than it used to be. Then again, certain words to do with racism are less acceptable. So things have changed for better and for worse.)

- Who you are with.

(Getting drunk with your best friend is socially acceptable. Doing the same with grandma, not so much.)

- Which country you’re in.

(It’s perfectly acceptable for German kids to casually use the word ‘Scheiße’. Seriously, the S-word is fine over there.)

- And which exact place you’re in.

(Let’s just say there are things you’d do in the bedroom that you wouldn’t do at the library.)

So, not only have I always found appropriate and inappropriate harder than right and wrong… I also trust them a lot less. You never know when the cultural ground may shift beneath you, or where it will go.

Right and wrong are so much simpler.

Of course, not everyone agrees.

Because the sad truth is this: there’s The Right Thing (which I’d like to think is obvious to most people) and then there’s The Done Thing. I’m not sure whether non-British people use that phrase, but “the done thing” is simply what’s socially acceptable to do.

E.g. “He’s annoying me, but I can’t slap him in the face. It’s not the done thing.”

So, now we’ve defined what “The Done Thing” is, picture yourself in this situation.

You’re walking down a crowded street, and another person is walking in the other direction. As they approach, you see that tears are streaming down their face. You have never met this person before, but your heart goes out to them. You’re tempted to say something nice to them because you’re a caring person, but you’re in a busy street in a town where you’re not really ‘supposed’ to talk to random people, since you don’t know each other.

Being totally, totally honest, what do you do?

This exact example happened to me three days ago. I’d bought my lunch and was heading back to the workplace, and I passed a teenage lad on the way. He was clearly crying.

Me being me, someone who loves helping vulnerable people and someone who’s good with teenagers, I wanted to say something positive to him. Just a one-sentence reassurance or something to lessen whatever he was going through.

Then the time came, and we walked right past each other in silence.

I’d like to think I was simply too slow to come up with something good. And there were plenty of “what if?”s in my head to slow me down- what if it would make him self-conscious? What if my words did more harm than good?

But a part of me is afraid that I’ve turned into an adult, and my questions were attempts to justify my inaction. Because adults, all too often, will only do The Right Thing if it also happens to be The Done Thing. After all, morals are so much easier to follow when they’re socially acceptable too.

I hope that lad ended up ok, but I’ll never know. He doesn’t have the faintest idea I cared either.

But it’s ok- we were both socially appropriate. And that matters to people.

Appropriateness is discreet.

A lot of being appropriate depends on how you say your words. For example:

It’s inappropriate to say “urgh, you should put some deodorant on because you smell really bad.”

But it’s fine to say “mate, you might want to freshen up a bit.”

Both of those sentences mean the exact same thing, but are interpreted differently. And without the social wisdom to know that two ways of saying something aren’t always interpreted the same, it’s easy to offend people.

Tone of voice is important too, and I’ve never been good at that. For example:

“Sorry I can’t help you.”

“Oh it’s fine, don’t worry about it.”

Is better than:

“Sorry I can’t help you.”

“Oh it’s fine. Don’t worry about it!”

…It’s difficult to phrase sarcasm over the internet, but you get my meaning.

Finally, being appropriate means knowing what not to say.

Well, this picture kind of sums it up.

Appropriateness is vague.

When we first learn about appropriate/inappropriate, we are made to understand that ‘appropriate’ is good, and ‘inappropriate’ is bad.

So ‘appropriate’ must have a lot in common with all the other good words, right? After all, kindness, compassion, friendliness and helpfulness all fit together so well.

Not quite. ‘Appropriate’ tries to sit down next to these other good words and share in their beautiful picnic, and it doesn’t work.

Because, being kind is not the same as being appropriate. For example:

From this kid’s perspective he was being kind, and kind is good. I can sympathise with autistic children’s confusion whenever someone tells them their kindness is ‘inappropriate’ (you know, the bad word. Which tells you you’re being bad.)

Heck, even being correct isn’t being appropriate! For example:

Some autistic people really just need things to be correct. That’s why a lot of us can’t bring ourselves to lie, and why a lot of us can’t stand liars. And again, I can sympathise with how alienated some autistic people feel when they’re told they’re ‘being bad’ by telling the truth.

Everyone has their own definition of ‘appropriate’.

And like I said before, some people use it like a weapon.

I once had friends whose kids went to the youth group I run. These boys led very action-packed lives, and (like me when I was younger) their parents had no problem with them climbing trees.

Now, I’m a huge advocate for tree-climbing. It’s adventurous, it’s challenging, it gives you a sense of achievement, the views are great, and it’s only ever dangerous if you’re not bothering to think about what you’re doing. (Unless you accidentally pick a tree with rotting branches, but that’s why I always rested my foot gently on each branch before pushing down. Just be careful and you won’t get hurt.)

But not all parents think that way. My friends were out with another family, who saw both sets of kids up a small tree (low enough that you could reach up and shake their hands) and went ballistic. My friends were told how wrong they were (there’s that word again, as if it was a moral thing) to let those boys climb that tree, and how it’s inappropriate to put children in such danger.

Then of course, there’s the divisive issue of hugs. I hugged a child in church last week because someone very close to us had died of cancer that morning. I knew the parents were fine with it, otherwise it simply wouldn’t have happened.

A career working with children has taught me to think carefully about these things. There’s a time and a place for hugs: in professional settings there are specific guidelines that you follow (and with good reason), and in social settings it depends on everyone’s collective opinion of what’s ‘appropriate’. Pick the fussiest person and go with their opinion. It’s the safest option.

In conclusion:

There are probably more reasons than the four stated above. But whenever you find yourself wondering why sometimes autistic people “just don’t get it” when it comes to social norms, think about these:

- Appropriateness is fluid.

And, as people who love consistency, how are we supposed to grasp something that’s ever-changing?

- Appropriateness is discreet.

And, as people who work better when people are direct, how are we supposed to grasp a hidden etiquette?

- Appropriateness is vague.

And, as people who need others to be specific, how are we supposed to even begin dealing with that vagueness?

- Finally, everyone has their own definition of ‘appropriate’.

And, as people who find others difficult to read, how are we supposed to learn new and different rules for each individual person?

A few things to think about.

Thanks for reading.

Chris Bonnello / Captain Quirk

-Chris Bonnello is a national and international autism speaker, available to lead talks and training sessions from the perspective of an autistic former teacher. For further information please click here (opens in new window).

Chris Bonnello on LinkedIn

Chris Bonnello on LinkedIn

Autistic Not Weird on Facebook

Autistic Not Weird on YouTube

Autistic Not Weird on Instagram

Copyright © Chris Bonnello 2015-2024

Underdogs, a near-future dystopia series where the heroes are teenagers with special needs, is a character-driven war story which pitches twelve people against an army of millions, balancing intense action with a deeply developed neurodiverse cast.

Book one can be found here:

Amazon UK | Amazon US | Amazon CA | Amazon AU

Audible (audiobook version)

Review page on Goodreads

Are you tired of characters with special needs being tokenised and based on stereotypes, or being the victims rather than the heroes? This novel series may interest you!

Are you tired of characters with special needs being tokenised and based on stereotypes, or being the victims rather than the heroes? This novel series may interest you!

Recent Comments