“My parents don’t accept that I am (or my child is) autistic. What should I do?”

This question ranks pretty high on the most frequently asked list. We just recently had a discussion about it on Autistic Not Weird’s Facebook page, and I think it’s about time I wrote a full article. (All links open in new windows, by the way.)

Most of us are used to people misunderstanding our autistic selves or relatives, but this is often from people we’re unlikely to see ever again. So what do you do when the lack of acceptance comes from within your own family?

Well, here’s my advice, for what it’s worth. This is written for the benefit of both autistic people themselves and their parents.

Before I begin though, I will stress that I almost certainly don’t know your family. As is often the case with these articles, pick and choose the advice that suits you and your situation.

Why do some families refuse to accept autism?

So first of all, let’s cover a couple of reasons why autism is overlooked in some families.

1. Generational differences

I often say that in thirty years’ time, autism will be widely accepted beyond a scale that we can comprehend right now. I say this because children are now introduced to difference at a very early age. I worked in a wide variety of schools, and it was surprisingly rare that I came across a class without any children with noticeable additional needs. And in the classes where the children’s neurological differences had been explained appropriately, their classmates were almost universally accepting and wanted to look after them well. (An excellent example of this strategy succeeding can be found in this example from Seriously Not Boring.)

Compare that to my generation, who grew up in the 1990s: I met my first noticeably disabled child at the age of ten, and I found it an eye-opening experience. But since I’d gone all through my life without seeing another child like him (he had Down’s Syndrome, by the way), it made me wrongly assume that children with special needs were incredibly rare.

And as for the less visible needs? Well, my dyslexic friends were thought of as stupid. The kids with ADHD were thought of as badly behaved. Kids like me were seen as having a “slightly odd personality”. (And yes, that is a literal quote from a report written about me in 1995.)

But I’m only 30. Compare my experiences to generations even further back! I once had a heated discussion with an old-ish man from my chess club, who was shocked and appalled that my school’s nonverbal autistic students wouldn’t call me “Mr Bonnello” or even “sir”.

Being naïve, I tried explaining learning difficulties to him- to no avail. And when I told him that forcing words from these students would be somewhere between impossible and damaging, his response was “well it never did us any harm”.

He was probably the inspiration for this picture I made.

That said, I’m unwilling to tar his whole generation with the same brush. One of my other clubmates, recently retired, is the grandfather of an autistic boy. He is perfectly clued up on what autism is and what it means, and a lack of exposure to autism in his youth has not prevented him one bit from understanding his grandson.

So why the difference between these two similar-aged men? I don’t know enough about their past to make any reliable comment, but I do wonder whether the grandfather had a wider variety of life experience as he grew up, or whether he is simply less resistant to the changing culture of our world.

Of course, it is tricky to educate people who are set in their ways (who are not always elderly, by the way!)- among those of any age who didn’t grow up with exposure to autism, there are those whose minds are open to change and others that aren’t.

But if it’s any comfort, once our kids grow up I genuinely believe we’ll no longer have this problem (or at the very least, not as much as we have it now).

2. Fear of stigma

As long as autism is considered A Bad Thing (which I personally object to, for some reason), there will always be the perception of stigma being attached to it- whether the stigma is real or imaginary.

And sadly, there are too many parents out there who refuse to get their child an autism diagnosis- or any of the support that would help their child- simply because they “don’t want the stigma of having a child with special needs”.

There are certain strong words I could use in response to this, but I’ll leave it at “stop being so bloody selfish, get off your backside and get your child the help they need. Because their needs are real with or without the diagnosis, and their support and provision must come before your ego.”

Sorry, needed to get that out.

As with the previous point, I honestly believe this problem will fade with time. The more accepting the general population is of autism, the less it will be seen by some as a problem that needs concealing.

But for now, the “different, not less” education of the masses needs to continue.

3. Not actually knowing what autism is

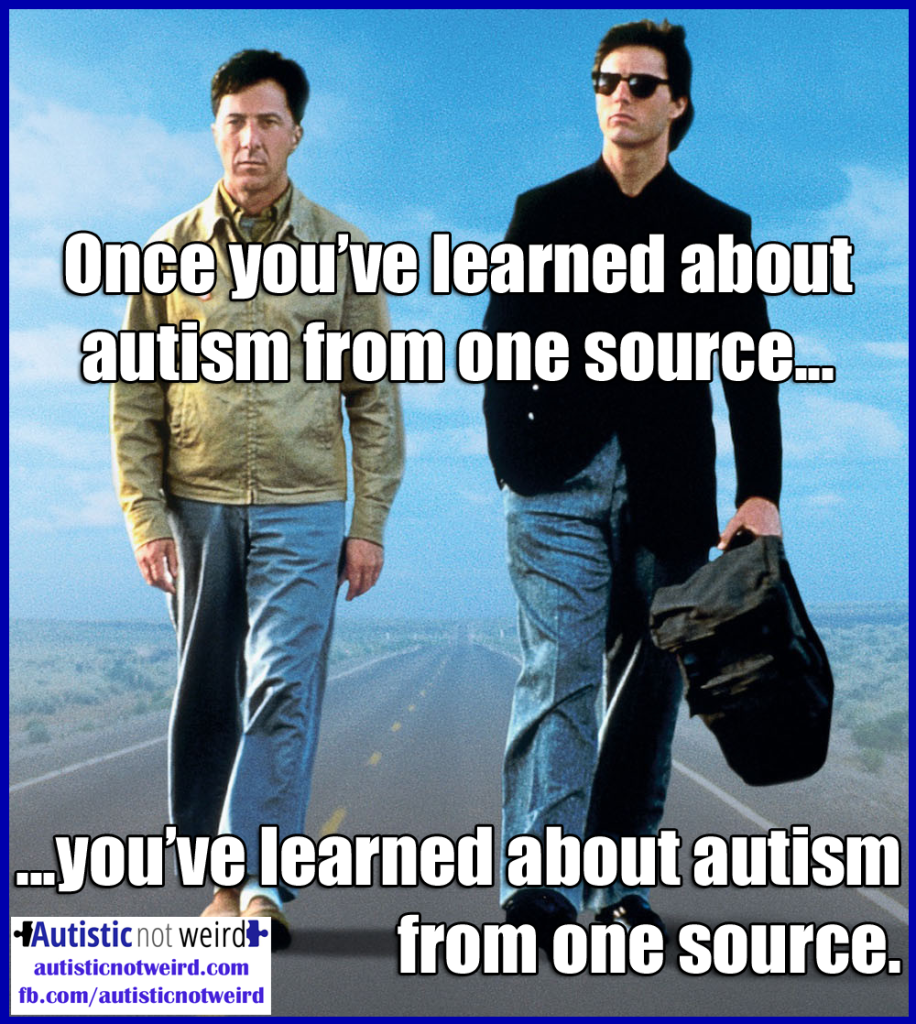

Some people are still stuck in the days of Rain Man (which was the best thing ever to happen to autism awareness… about thirty years ago).

Some people have got their knowledge from more accurate source material, like the amazing The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time, but based their entire understanding of autism on that one source. And that’s how stereotypes are created.

A few years after telling my friends I was autistic, I told them about my job in special education, and one of my friends answered with “really? Some people with autism can’t talk?!”

I would never call this friend ignorant, because of her keenness to learn (which, as I often say, is literally the opposite of ignorance!). But despite that keenness, I became very aware that because I was the only autistic person she knew, I was the source of her whole understanding of it.

So after that, I started talking more about autistic people who were different to me.

So that’s another reason why some family members (or people in general) may not accept the autism in their family. Some don’t deny it through ignorance or shame, but simply because they’re uninformed about the huge variety of autistic people that are out there. For example, if their understanding of autism is ‘nonverbal with severe learning difficulties’, they may not recognise autism in a seven-year-old who can read novels but is intensely uncomfortable with routine change.

4. Seeing autism as an ‘excuse’

Yep, we all knew this point was coming. Let’s get it over with.

In my last article, I went to great effort to differentiate between autism being a valid reason and being used as an excuse. There are massively important differences. But unfortunately, to the untrained eye tantrums and meltdowns often look similar. (Just the same as ADHD-driven behaviour looks similar to ‘kids having no discipline’, to people who have no experience in telling the difference.)

Particularly when combined with the last point- when the autistic family member does not match up with the stereotypes- it’s only a hop, skip and a jump to “you’re just using it as an excuse.”

This is very damaging, by the way. Partly because they’re being hurtful to a family member with genuine unrecognised struggles, but also because they might actually convince them. And that could lead to an autistic person growing up to believe they’re defective, which is a dreadful thing (as many of my followers will tell you, having been through it themselves).

5. Seeing themselves in the autistic person

I’d like to thank Kirsty from the Facebook community for pointing this out in discussion, because it didn’t actually occur to me. But it’s absolutely true.

I’ve heard from a number of parents who tell a similar story: that they learned about their own autism/Asperger’s while their child was being diagnosed. For many of these parents, they learned something about themselves and felt more able to help their autistic son/daughter afterwards.

But of course, among those who see autism as A Bad Thing, the natural response is resistance. Be aware of this- because if they’re phobic of being autistic and see a lot of themselves in their child (for example), repeatedly telling them their child is autistic could be the equivalent of repeatedly telling them that they’re autistic.

6. ‘Positive’ reasons

A little extra note (and sorry for referencing this, Mum and Dad, but trust me).

When I first ‘came out’ to my parents about suspecting I had Asperger’s (in 2009), they didn’t believe me.

And why not? Because each of my personal quirks that I referred to as an Asperger’s trait had been interpreted through the years of ‘Chris being Chris’.

I came to realise something quite positive. The reason they were doubtful was because they had spent 25 years to that point knowing me as a person. They were reluctant to see my symptoms as being anything other than the Chris they knew and loved growing up. Despite the psychologist interventions and early speech therapy, they had always seen me in terms of my quirky personality and nothing else.

Despite their doubts, they listened to me. And once I explained my reasoning- and the reasoning of my teacher colleagues who had worked it out for themselves (and also my sister, which was handy)- they came to accept that I was autistic. Since then, they’ve never been anything but supportive.

In fact, Mum recently said to me:

“Actually, given that you faced these challenges as a child- and you didn’t even know where they came from- that actually makes us even prouder of you.”

So it is possible for the doubt to come from positive intentions. And in my personal experience, it’s those people who are more likely to be open to listening and learning.

Oh, and I’ll quote a follower here who left this comment in a recent discussion. One of the ‘positive’ reasons for disbelieving is they think the autistic person is brilliant, and they don’t (yet) see how autism can be a non-negative thing.

I’ve had people tell me about my now 8 year old son, “there’s nothing wrong with him” to which I answer, “of course not, but he is Autistic and I expect you to respect that.” Seems to settle things nicely.

-Tracey

So what should I do if my family doesn’t believe me?

Well, the reason I wrote all of the above is because it’s the first thing that needs establishing. Why doesn’t the family member believe you?

Do you (or your child) not match the stereotypes? Are they afraid of the stigma? Are their perceptions of autism inaccurate? Are there other family matters at play which may cloud their judgement? More than one of these?

Once you have some idea of their reasons, it may help you work out where to go next.

I’m going to present two possible scenarios. Your relative may land somewhere between the two. Honestly, I’d recommend reading both scenarios with equally attention and taking the relevant advice from each.

You might be in a position to educate them.

Depending on how receptive your family is (and their reasons for doubting), you may end up being the means by which they learn about autism.

But there’s a way of doing it. And a way of not doing it.

I remember being very open about my Christian faith at university (trust me, I’m going somewhere with this). A big bunch of us were, and plenty of us were quite keen on discussing the Gospel. Myself included- surprisingly, given my social awkwardness. And in my time there, I saw how to do it and how not to do it.

Surprisingly, there are parallels with talking about autism to a ‘non-believer’.

If, for example, you go to a non-Christian and start talking loudly about the perspicuity of Calvinistic ideals or the specifics of the liturgy of the sacrament or how Jesus was a propitiation for man’s iniquities, don’t be surprised if they lose interest. (Seriously, even other Christians would.)

But talk gently about the basic principles, how they apply to you, and how they impact your perspective on life, and that’s where the learning happens. Even if they don’t agree with you, they often leave the conversation closer to understanding your perspective.

Likewise- don’t overload the relative with words, phrases and concepts they’ve never heard of. If you start going ASD, IEP, AAC, ABA, ODD, PDD-NOS, BIP/BMP all over the place, expect confusion rather than understanding. Because, even if they end up believing you, unfamiliar language will not help them understand the person behind the autism.

One of the very first things I ever learned in teaching was “learn where they are, then start where they’re at.” So that would be my advice for teaching anyone about autism: find out what they already know, and go from there.

An extra point- generally speaking, people trust the word of professional psychiatrists. And even if they don’t, sentences beginning with “the doctor says…” usually carry more weight than “I think…”

So, if you or your child has the backing of a qualified doctor, quote them. If there’s a printed report, offer them a glance.

But they might be completely closed to discussion.

Sadly, it might be the case that your relative is closed to all conversation about the subject.

And if that’s the case, there’s little you can do about it. We can try being positive influences over people, but one thing we can never do is make other people’s choices for them.

So if they choose to not accept autism in their family, for whatever reason, how do you help them to understand you or your child?

My immediate advice is to keep talking about the struggles, but talk about them in non-autistic terms.

For example, maybe:

“I’m struggling because the music’s too loud.”

Is more likely to have a positive impact than:

“I’m struggling to concentrate because my autism makes me sensitive to noise.”

I know how ugly it sounds, cutting autism out of the sentence. Especially if it’s a major part of your (or your child’s) identity. But this strategy does get the other person closer to understanding the autistic family member and their needs. In certain cases it’s better to concentrate solely on helping them to understand the person, and leave the ‘autism battle’ for another day.

And again- whether or not you mention autism- quote the details from the professionals. If you have the backing of a psychiatrist, use it where you can.

Finally, I’m going to offer the “you’re not alone” advice again.

Seriously, right from starting Autistic Not Weird this was a surprisingly common question. And as isolating as autism often feels, I hope you’re able to see that there are plenty of other people out there who share your frustrations. Finding and talking to these people can be quite therapeutic, as well as a chance to learn how to deal with it. (If you’re not already in ANW’s Facebook community, you’ll find plenty of these people there.)

As frustrating as it is when you have to endure those who don’t accept autism, it’s important to focus on socialising with people who do accept it!

And to finish, the usual bullet-point list:

- Establish why they don’t believe you/your child is autistic.

- If they’re comfortable with discussing the subject, pitch your conversation at their current understanding.

- If you have the backing of a professional, quote the professional.

- If they won’t talk about autism, talk about the struggles without mentioning the diagnosis.

- You are not alone in not being believed. But the tide is turning in the right direction. I promise.

I hope this helps some of you.

Chris Bonnello / Captain Quirk

-Chris Bonnello is a national and international autism speaker, available to lead talks and training sessions from the perspective of an autistic former teacher. For further information please click here (opens in new window).

Chris Bonnello on LinkedIn

Chris Bonnello on LinkedIn

Autistic Not Weird on Facebook

Autistic Not Weird on YouTube

Autistic Not Weird on Instagram

Copyright © Chris Bonnello 2015-2024

Underdogs, a near-future dystopia series where the heroes are teenagers with special needs, is a character-driven war story which pitches twelve people against an army of millions, balancing intense action with a deeply developed neurodiverse cast.

Book one can be found here:

Amazon UK | Amazon US | Amazon CA | Amazon AU

Audible (audiobook version)

Review page on Goodreads

Cover photo by Jordan Whitt on Unsplash

Are you tired of characters with special needs being tokenised and based on stereotypes, or being the victims rather than the heroes? This novel series may interest you!

Are you tired of characters with special needs being tokenised and based on stereotypes, or being the victims rather than the heroes? This novel series may interest you!

Recent Comments